Coffee Rides the Rails

Back in the days when you could find coffee perfection in any top restaurant, you could also be gentled into caffeine bliss during any of several top notch train runs across America.

It was all part of the taming of this land that rail travel be as luxurious as possible, as a way of compensating the developers of our country for the enormous spreads of land, across which we now soar in a matter of forgettable hours.

You’d never know on Amtrak that the crack Twentieth Century, hurdling passengers down the tails at 90 miles per hour, served an excellent blend of Brazilian and Mocha. Coffee brewed in a sparkling clean urn was made fresh on the hour by the book (one pound of coffee per pot) plus a copious extra handful of fresh grounds in order to give it that extra flavor expected by travelers who were issued both the New York Times and Wall Street Journal each morning in its diner.

Waiters brought fresh coffee cream (18 percent butterfat) sourced from a small Connecticut farm.

A glance at a menu from a golden age diner shows no special hype about the coffee. Naturally, a passenger would only expect a train with the best food to serve the finest beverages aboard. As for the railroad management, every possible consideration was given to keeping business and tourist travel at the peak of perfection in order to maintain an image of efficient supportive of the really profitable freight business.

A discussion with Dana Ishman, a dining car chief steward with the Amtrak, but also a real historian, proved instructive, Ishman told me that each train had its specialty. “The Nebraska Zephyr held a reputation for the best, thickest steaks and served only two pounds russet potatoes. The Denver trains actually stopped on a train trestle over a river where local fishermen handed up fresh-caught trout”.

I asked Ishman what coffee his train used when the Burlington operated it… “They used a blend from a roaster in Chicago who delivered the coffee direct to the train just before departure time”, he offered. I then asked him if they made the coffee particularly strong. “Not by my standards. But then railroad people like good hearty coffee.” Then he volunteered, “If you ask my opinion, the key was they never let the coffee sit and the urn was always scrupulously clean. You go to a restaurant now and often the coffee is just sitting there for a few hours, especially if it’s an off-hour. That just wouldn’t happen on any train of mine!”

During this last statement the otherwise soft-spoken Ishman took on an authoritative tone that matched the images the people who ran “restaurants on wheels? held during these years. According to legend, Great Northern’s chief steward William Kurthy ran his trains with a temper to match the piping hot coffee he served. Kurthy would march up and down the aisle between tables and inspect the coffee cups on them. If one was empty, a single flaring look from Kurthy commanded an immediate refill, from an urn cleaned nightly as the passengers slept. Kurthy, or “Wild Bill”, as he became known, had a mesmerizing but maniacal control over his domain. Never content with the well-earned reputation for excellence on his trains, he had a habit of publicly and ceremoniously firing waiters and other servers for the slightest infraction, always at the height of the dinner hour. These exhibitionist dramas were always much appreciated by the diners, who boarded the trains in knowing expectation of both the level of service and Kurthy’s national fame as a America’s most fanatic food service operator. Lest you think he was tough just on the hired help, Kurthy was perfectly suited to bully passengers as well.

In great railroad chronicler Lucious Beebe‘s words, “Tiny old ladies who ordered tea were forced to eat T-Bone steaks smothered in mushrooms, and retiring passengers, numb with good living, spoilt by Kurthy’s team, were met at bedtime by a grinning waiter with a foot-high stack of rare roast beef sandwiches and glasses of half and half.” Glasses of half and half?!?!?

My research shows that coffee during the great rail era was simply expected to be top drawer. Before the age of espresso/latte evening repasts, the after dinner blend of choice was 1/3rd Mocha to 2/3rds Java. This staple was considered the staple and the Broadway limited served it. Rich Colombian or other fine Latin American coffees were the wake up call. Film star Spencer Tracy‘s regimen was to be awakened at 5AM, whereupon he drank an entire pot of specially-made strong black coffee (Tracy reportedly hated weak drinks of any kind) and then returned to sleep for another hour. Orson Welles has his dwarf manservant boarded the train with his own blend, heavily laden with beans from Sumatra in addition to the twenty or so books with which he always traveled. Year’s predating the controversial McDonald’s scald trial were several lawsuits during the railroads’ heyday where passengers claimed injury due to waiters spilling hot coffee on them during the sudden jerks as the trains rolled uneasily on rugged track sections. Rail workers too, unprotected by government worker’s compensation, were required to sue for their on-the-job injuries as they remain today.

The great coffee merchants of the day, strategically located in high visibility railroad towns went to extraordinary ends to serve the best fresh coffee to their customers. Dallis Brothers in New York. Stewarts and the House of Millar in Chicago. Boyds in Portland. Hills Brothers (then using only high grade arabicas) in San Francisco. In the days when famed author E. B. White was once quietly asked to leave the diner because a torn sock and a spot of flesh had been spied just above his shoe top, a cheap robusta coffee would have been denied access to any respectable railroad diner. Even predating the great dining cars were the along-the-route food oases operated by British emigrant, Fred Harvey. A glance at a Harvey company training manual describes the necessary ingredients to a successful cup of coffee, Fred Harvey-style: “A great cup of coffee is brewed with fresh coffee, made strong and served within minutes of brewing, piping hot.”

Does the SCAA Brew Chart Need To Be Changed?

The Specialty Coffee Association of America endorses an objective measurement based upon an analysis of some brewed coffee. It measures the total number of dissolved solids as an analog of coffee flavor. While no one, including the SCAA, claims this is a perfect measurement of true coffee taste, nor to they claim it’s the taste everyone agrees to be perfect, the standards was established on the principle that we have to start somewhere and to help create some sort of objective standard for the industry to use to compare taste intensity.

What good’s an industry if it doesn’t attempt to establish and promote good standards? I think that’s a fair question and it’s to the SCAA’s credit that they are trying to do something to standardize measurements. But, here are some questions I have for the SCAA.

- Are they doing a service if the standards really don’t represent the taste people really want in their coffee?

- How do they know the standards are applicable to most public coffee drinkers?

- Is the current dissolved solids test really accurate in measuring what consumers call coffee taste?

- Has the espresso drink trend (really the café latte trend) caused consumer coffee taste expectations to dramatically change?

Where the Standards Came From

The SCAA’s standards are pretty clear. They suggest 18 to 22% weight of the ground coffee’s oils to extracted to a brew, which will, by their calculations become a beverage containing 1.15 to 1.35 percent dissolved solids. In effect, it’s like making a lemonade and saying we want this percentage of a lemon to be used and the resulting lemonade should contain thus amount of juice in its makeup. The standards were established by a committee of (probably) pretty learned and sincere coffee people. I’ve heard negative comments that the standards were simply a way to sell more coffee, but (and I’ve never sold a bean in my life) I think that’s an unfair allegation. These were people who recognized that a full flavored, developed cup of brew was actually not bitter and that many food service operators and home users were habitually destroying coffee’s flavor by over-extracting undersized portions of ground coffee. Their intentions were, in my opinion, good and honorable.

Now to a problem: How do you take this noble measurement? The most obvious method was chosen, and that’s using a hydrometer which measures water and then measures the same water’s density once it has been changed, in this case water that’s been changed into brewed coffee. Roast and bean variety will affect density It’s a pretty ingenious idea, and the industry seems to agree that it’s a reasonable way to “see” how much coffee taste is in there. It does not answer questions such as if the coffee flavor’s strength altered by such things as roast or varietal or any number of other factors. The test is not able to tell if the coffee tastes good. That is not its role. So, within the parameters of what it’s designed to do, it seems the test can achieve a goal.

But, what happens if tastes change? Do you think that they do? Let’s take wine. What if we found out that the French wine board set standards for pH and alcohol in wine? Would those big California clarets meet those standards? I think not, and that is part of what has happened. Like it or not, the fun and profit of espresso-based beverages has moved the American coffee drinking public away from the light-roasted vacuum-brewed cup of coffee that this august panel decided was a great cup of coffee back many years ago. To go back to the wine analogy for a moment, the French oenophile who developed the years ago wine standards would have spit out the latest Kendall-Jackson Chardonnay, although some of those fine old French firms have taken to selling their Chardonnay as motor fuel due to changing tastes.

What happens when roasts change? Frank Chambers did some research on measuring coffee strength and discovered that different varieties and different roasts brewed using the same formula, brewed in the same coffee brewer, will give different results on the SCAA chart. The short cut way to say it is that dark roasts will provide stronger coffee and coffees from different growing regions provide more or less strength. In fact, the chart’s developers specified that only one variety roasted to one roast color be used for testing.

My concern is that the American Specialty Coffee Association might be inadvertently imposing a no-longer valid standard. There are only two current coffee brewer manufacturers known to me who ever mention the SCAA’s standards: Kitchen Aid and Bunn-O-Matic. Kitchen Aid designed their wonderful 4-cup brewer several years ago following the SCAA’s standards only to be denied certification when their brewer’s heating element failed to jack up the brewing temperature above 195 Fahrenheit during its first minute of brewing. While I publicly disagreed with this because I think the temperature standards are too narrow, I have to applaud the SCAA for at least sticking to their guns and having some standards. Meanwhile, Bunn keeps putting out coffee brewers that do meet the standards, but they continue to lose competitions won by brewers that don’t.

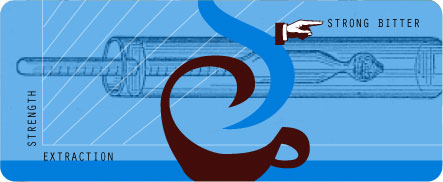

The Coffee Brewing Chart

Part of the SCAA’s brewing standard was the creation of a chart that showed where a coffee’s flavor strength, as measured using a hydrometer, appeared in relation to its strength versus bitterness, versus body. Although interesting to only the most advanced home users, the idea was to get the commercial coffee servers to “get religion” and see that their adherence to the SCAA’s standards would produced a full-flavored but not bitter cup. The chart, which is difficult if not impossible for most people to understand (even in the industry), contains a box on it that represents the ideal balance of flavor strength, so-called “development” (supposedly “which” flavors), lack of bitterness (over development?) and thrift or economy. The message is clear: brew coffee that falls into the box and you’ll be making people’s taste buds happy. We know, we’re the Specialty Coffee Association. The last tests I saw of various consumer coffee brewers, only one brand made it into the box and it was a Bunn-O-Matic. None of the others did, and the list was extensive. So, either the other manufacturers are ignoring the SCAA or they are incapable of meeting the standards or don’t know how to measure their machines. I’m guessing it’s number one and that they just don’t care or thing anyone will notice.

Now, I just gave Bunn a free ride. But, how about them? Why did they fail to impress Cooks Illustrated? Why do high-end roasters who want their customers to own the best brewer often recommend other models, some of the same ones that don’t brew coffee that fall near the SCAA’s box? You might speculate that the other brewer manufacturers don’t care or know how to test, but the high end bean sellers do care and do know how to test. This tells us in a dramatic way that those bean sellers don’t think their customers want coffee that’s “in the box”—the SCAA’s box at any rate.

I’ve tested the Bunn machine. My test results confirm what the SCAA’s box says. The Bunn delivers a nice no-bitterness cup of coffee, one that is very full flavored as far as acidity. My taste observations are that many consumers, including some who buy very expensive beans and grind them carefully before brewing, are now weaned on espresso. The level of bitterness that bothered an honest coffee merchant or taster in 1970 no does not bother this end-user and in fact he desires it. I challenged Cook’s Illustrated on some of their methodology but I spoke extensively with Cook’s Illustrated’s Lisa McManus and they did consult with some honest and notable coffee experts before drawing her conclusions. I think she represents fairly what many consumers would taste. Cook’s Illustrated did not report performing any total dissolved solids tests.

In my opinion, we have here an honest mistake in the making. The sad thing is several industry leaders are trying to do the right thing. Two of the industry’s most noble and honest manufacturers are losing sales because they are adhering to seriously deficient and possibly outdated standards. And, the SCAA is failing to reexamine and update their standards given emerging consumer taste pattern changes.

The risk is what happened to me when I followed the outdated road maps on my GPS this summer. I didn’t reach my goal and someone without guidance did.

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.