The Specialty Coffee Association of America endorses an objective measurement based upon an analysis of some brewed coffee. It measures the total number of dissolved solids as an analog of coffee flavor. While no one, including the SCAA, claims this is a perfect measurement of true coffee taste, nor to they claim it’s the taste everyone agrees to be perfect, the standards was established on the principle that we have to start somewhere and to help create some sort of objective standard for the industry to use to compare taste intensity.

What good’s an industry if it doesn’t attempt to establish and promote good standards? I think that’s a fair question and it’s to the SCAA’s credit that they are trying to do something to standardize measurements. But, here are some questions I have for the SCAA.

- Are they doing a service if the standards really don’t represent the taste people really want in their coffee?

- How do they know the standards are applicable to most public coffee drinkers?

- Is the current dissolved solids test really accurate in measuring what consumers call coffee taste?

- Has the espresso drink trend (really the café latte trend) caused consumer coffee taste expectations to dramatically change?

Where the Standards Came From

The SCAA’s standards are pretty clear. They suggest 18 to 22% weight of the ground coffee’s oils to extracted to a brew, which will, by their calculations become a beverage containing 1.15 to 1.35 percent dissolved solids. In effect, it’s like making a lemonade and saying we want this percentage of a lemon to be used and the resulting lemonade should contain thus amount of juice in its makeup. The standards were established by a committee of (probably) pretty learned and sincere coffee people. I’ve heard negative comments that the standards were simply a way to sell more coffee, but (and I’ve never sold a bean in my life) I think that’s an unfair allegation. These were people who recognized that a full flavored, developed cup of brew was actually not bitter and that many food service operators and home users were habitually destroying coffee’s flavor by over-extracting undersized portions of ground coffee. Their intentions were, in my opinion, good and honorable.

Now to a problem: How do you take this noble measurement? The most obvious method was chosen, and that’s using a hydrometer which measures water and then measures the same water’s density once it has been changed, in this case water that’s been changed into brewed coffee. Roast and bean variety will affect density It’s a pretty ingenious idea, and the industry seems to agree that it’s a reasonable way to “see” how much coffee taste is in there. It does not answer questions such as if the coffee flavor’s strength altered by such things as roast or varietal or any number of other factors. The test is not able to tell if the coffee tastes good. That is not its role. So, within the parameters of what it’s designed to do, it seems the test can achieve a goal.

But, what happens if tastes change? Do you think that they do? Let’s take wine. What if we found out that the French wine board set standards for pH and alcohol in wine? Would those big California clarets meet those standards? I think not, and that is part of what has happened. Like it or not, the fun and profit of espresso-based beverages has moved the American coffee drinking public away from the light-roasted vacuum-brewed cup of coffee that this august panel decided was a great cup of coffee back many years ago. To go back to the wine analogy for a moment, the French oenophile who developed the years ago wine standards would have spit out the latest Kendall-Jackson Chardonnay, although some of those fine old French firms have taken to selling their Chardonnay as motor fuel due to changing tastes.

What happens when roasts change? Frank Chambers did some research on measuring coffee strength and discovered that different varieties and different roasts brewed using the same formula, brewed in the same coffee brewer, will give different results on the SCAA chart. The short cut way to say it is that dark roasts will provide stronger coffee and coffees from different growing regions provide more or less strength. In fact, the chart’s developers specified that only one variety roasted to one roast color be used for testing.

My concern is that the American Specialty Coffee Association might be inadvertently imposing a no-longer valid standard. There are only two current coffee brewer manufacturers known to me who ever mention the SCAA’s standards: Kitchen Aid and Bunn-O-Matic. Kitchen Aid designed their wonderful 4-cup brewer several years ago following the SCAA’s standards only to be denied certification when their brewer’s heating element failed to jack up the brewing temperature above 195 Fahrenheit during its first minute of brewing. While I publicly disagreed with this because I think the temperature standards are too narrow, I have to applaud the SCAA for at least sticking to their guns and having some standards. Meanwhile, Bunn keeps putting out coffee brewers that do meet the standards, but they continue to lose competitions won by brewers that don’t.

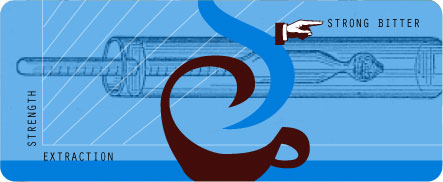

The Coffee Brewing Chart

Part of the SCAA’s brewing standard was the creation of a chart that showed where a coffee’s flavor strength, as measured using a hydrometer, appeared in relation to its strength versus bitterness, versus body. Although interesting to only the most advanced home users, the idea was to get the commercial coffee servers to “get religion” and see that their adherence to the SCAA’s standards would produced a full-flavored but not bitter cup. The chart, which is difficult if not impossible for most people to understand (even in the industry), contains a box on it that represents the ideal balance of flavor strength, so-called “development” (supposedly “which” flavors), lack of bitterness (over development?) and thrift or economy. The message is clear: brew coffee that falls into the box and you’ll be making people’s taste buds happy. We know, we’re the Specialty Coffee Association. The last tests I saw of various consumer coffee brewers, only one brand made it into the box and it was a Bunn-O-Matic. None of the others did, and the list was extensive. So, either the other manufacturers are ignoring the SCAA or they are incapable of meeting the standards or don’t know how to measure their machines. I’m guessing it’s number one and that they just don’t care or thing anyone will notice.

Now, I just gave Bunn a free ride. But, how about them? Why did they fail to impress Cooks Illustrated? Why do high-end roasters who want their customers to own the best brewer often recommend other models, some of the same ones that don’t brew coffee that fall near the SCAA’s box? You might speculate that the other brewer manufacturers don’t care or know how to test, but the high end bean sellers do care and do know how to test. This tells us in a dramatic way that those bean sellers don’t think their customers want coffee that’s “in the box”—the SCAA’s box at any rate.

I’ve tested the Bunn machine. My test results confirm what the SCAA’s box says. The Bunn delivers a nice no-bitterness cup of coffee, one that is very full flavored as far as acidity. My taste observations are that many consumers, including some who buy very expensive beans and grind them carefully before brewing, are now weaned on espresso. The level of bitterness that bothered an honest coffee merchant or taster in 1970 no does not bother this end-user and in fact he desires it. I challenged Cook’s Illustrated on some of their methodology but I spoke extensively with Cook’s Illustrated’s Lisa McManus and they did consult with some honest and notable coffee experts before drawing her conclusions. I think she represents fairly what many consumers would taste. Cook’s Illustrated did not report performing any total dissolved solids tests.

In my opinion, we have here an honest mistake in the making. The sad thing is several industry leaders are trying to do the right thing. Two of the industry’s most noble and honest manufacturers are losing sales because they are adhering to seriously deficient and possibly outdated standards. And, the SCAA is failing to reexamine and update their standards given emerging consumer taste pattern changes.

The risk is what happened to me when I followed the outdated road maps on my GPS this summer. I didn’t reach my goal and someone without guidance did.

Kevin: Thanks for a well thought out and important article. The whole coffee standards issue is a mine field with different cup sizes used from NA to EU and brewers too. The tastes have changed and will keep changing so how do we come up with a standard or is it even possible? With brew strength not only being a function of roast, bean, brew method but customers taste are we better off going with a different standard? Should we base it on “shots” as the coffee weight per espresso shot is pretty even world wide. If you ask almost any coffee drinker how they order a beverage at a coffee shop they will say x shots in a type of drink, so should brewed be referenced the same way?

I like the issues you have brought up in this blog. There are many variables that can produce a bad cup of coffee and still fall into the ideal SCAA box. Plus, how many consumers can afford a coffee TDS meter? All the variables that result in a great cup of coffee should be recorded and shared. And then duplicated by others to collaborate the results. And even then, each individual will need to adjust the recipe to their particular taste profile.

Thanks, Suzan. The TDS reading really doesn’t tell the whole story of flavor. It is as Doug says in his comment, a guideline. Everyone wants a gas gauge, an altimeter or yardstick. TDS is more of an analog, not nearly so precise. At best it offers a good starting place, a way to start a dialogue, not end it.

Good summary. Good thoughts, and right on the mark, though being a coffee geek makes it easy to go overboard calculating and forget why we brew the stuff to start with. But for the casual reader/coffee drinker not very relevant. People brew coffee to their liking, or at least their concept of how much to put in. After a long run doing the same thing they probably get to the brew ratios and parameters they want. The SCAA standard is difficult to nail down , but it puts a stick in the mud. We need a stick in the mud (measuring reference). That’s all it is. Even though others have over analyzed it and tech geeks have gone bonkers sweating it, for a casual drinker, it is all fluff.

For a serious drinker, I trust they can distinguish the flavors. If you think it would be a good idea to adjust standards up becasue people enjoy a stronger cup of coffee nowadays that would be fine, but really serve no purpose. The reference point is there. If a manufacturer wants to design their machine based on this fine, but any good manufacturer knows that they should run consumer trials to target the tastes of their segment. The SCAA standards reflect pretty accurately the concentration of a typical American coffee; are a great point of departure. To adjust the standards will only muddy the coffee at this point. To the other commentator, you don’t need a TDS meter to measure your coffee dissolved solids. I checked mine by collecting carefully all the grinds. I run 19.5 to 20%, and found that by drying the grinds in an oven at 210 F. It took about 4 to 4.5 hours to get all the water out. This agreed with a refractometer and TDS correlations but was actually much more precise. Now, I have a better way to check this, as the instrumental TDS, conductivity or refrative index are not as relianble in my experience for my purpose. I simply get an aluminum pie pan and casually dump ten coffees (of know weights of pre-extracted beans) into it, and beforehand get an accurate tare weight. Then one run in the oven and I get my average cup percent extraction. That’s where the 19.5 – 20% is from. When I used the instrument, it was dubious whether it was any better than a range of 1% (meaning something at 20% could easily show as 19.5 to 20.5). Anyway, after all the geekery, I know I like my coffee at 1.30% and then add the sugar later. The standards served their purpose, and by coincidence I am in their range. At the ‘strong’ end, but honestly I don’t know what else I could want from this. Perhaps should be thought of as a guideline, and everyone can be happy.

Agreed. Thank you for your comment.