by Coffee Kevin | Nov 8, 2011 |

The Specialty Coffee Association of America endorses an objective measurement based upon an analysis of some brewed coffee. It measures the total number of dissolved solids as an analog of coffee flavor. While no one, including the SCAA, claims this is a perfect measurement of true coffee taste, nor to they claim it’s the taste everyone agrees to be perfect, the standards was established on the principle that we have to start somewhere and to help create some sort of objective standard for the industry to use to compare taste intensity.

What good’s an industry if it doesn’t attempt to establish and promote good standards? I think that’s a fair question and it’s to the SCAA’s credit that they are trying to do something to standardize measurements. But, here are some questions I have for the SCAA.

- Are they doing a service if the standards really don’t represent the taste people really want in their coffee?

- How do they know the standards are applicable to most public coffee drinkers?

- Is the current dissolved solids test really accurate in measuring what consumers call coffee taste?

- Has the espresso drink trend (really the café latte trend) caused consumer coffee taste expectations to dramatically change?

Where the Standards Came From

The SCAA’s standards are pretty clear. They suggest 18 to 22% weight of the ground coffee’s oils to extracted to a brew, which will, by their calculations become a beverage containing 1.15 to 1.35 percent dissolved solids. In effect, it’s like making a lemonade and saying we want this percentage of a lemon to be used and the resulting lemonade should contain thus amount of juice in its makeup. The standards were established by a committee of (probably) pretty learned and sincere coffee people. I’ve heard negative comments that the standards were simply a way to sell more coffee, but (and I’ve never sold a bean in my life) I think that’s an unfair allegation. These were people who recognized that a full flavored, developed cup of brew was actually not bitter and that many food service operators and home users were habitually destroying coffee’s flavor by over-extracting undersized portions of ground coffee. Their intentions were, in my opinion, good and honorable.

Now to a problem: How do you take this noble measurement? The most obvious method was chosen, and that’s using a hydrometer which measures water and then measures the same water’s density once it has been changed, in this case water that’s been changed into brewed coffee. Roast and bean variety will affect density It’s a pretty ingenious idea, and the industry seems to agree that it’s a reasonable way to “see” how much coffee taste is in there. It does not answer questions such as if the coffee flavor’s strength altered by such things as roast or varietal or any number of other factors. The test is not able to tell if the coffee tastes good. That is not its role. So, within the parameters of what it’s designed to do, it seems the test can achieve a goal.

But, what happens if tastes change? Do you think that they do? Let’s take wine. What if we found out that the French wine board set standards for pH and alcohol in wine? Would those big California clarets meet those standards? I think not, and that is part of what has happened. Like it or not, the fun and profit of espresso-based beverages has moved the American coffee drinking public away from the light-roasted vacuum-brewed cup of coffee that this august panel decided was a great cup of coffee back many years ago. To go back to the wine analogy for a moment, the French oenophile who developed the years ago wine standards would have spit out the latest Kendall-Jackson Chardonnay, although some of those fine old French firms have taken to selling their Chardonnay as motor fuel due to changing tastes.

What happens when roasts change? Frank Chambers did some research on measuring coffee strength and discovered that different varieties and different roasts brewed using the same formula, brewed in the same coffee brewer, will give different results on the SCAA chart. The short cut way to say it is that dark roasts will provide stronger coffee and coffees from different growing regions provide more or less strength. In fact, the chart’s developers specified that only one variety roasted to one roast color be used for testing.

My concern is that the American Specialty Coffee Association might be inadvertently imposing a no-longer valid standard. There are only two current coffee brewer manufacturers known to me who ever mention the SCAA’s standards: Kitchen Aid and Bunn-O-Matic. Kitchen Aid designed their wonderful 4-cup brewer several years ago following the SCAA’s standards only to be denied certification when their brewer’s heating element failed to jack up the brewing temperature above 195 Fahrenheit during its first minute of brewing. While I publicly disagreed with this because I think the temperature standards are too narrow, I have to applaud the SCAA for at least sticking to their guns and having some standards. Meanwhile, Bunn keeps putting out coffee brewers that do meet the standards, but they continue to lose competitions won by brewers that don’t.

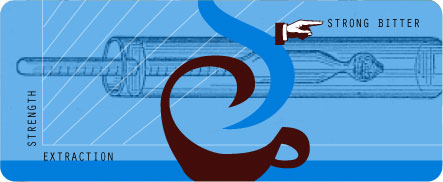

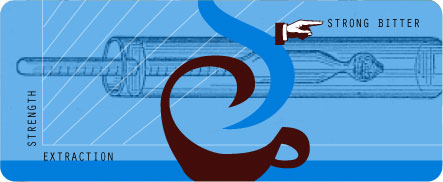

The Coffee Brewing Chart

Part of the SCAA’s brewing standard was the creation of a chart that showed where a coffee’s flavor strength, as measured using a hydrometer, appeared in relation to its strength versus bitterness, versus body. Although interesting to only the most advanced home users, the idea was to get the commercial coffee servers to “get religion” and see that their adherence to the SCAA’s standards would produced a full-flavored but not bitter cup. The chart, which is difficult if not impossible for most people to understand (even in the industry), contains a box on it that represents the ideal balance of flavor strength, so-called “development” (supposedly “which” flavors), lack of bitterness (over development?) and thrift or economy. The message is clear: brew coffee that falls into the box and you’ll be making people’s taste buds happy. We know, we’re the Specialty Coffee Association. The last tests I saw of various consumer coffee brewers, only one brand made it into the box and it was a Bunn-O-Matic. None of the others did, and the list was extensive. So, either the other manufacturers are ignoring the SCAA or they are incapable of meeting the standards or don’t know how to measure their machines. I’m guessing it’s number one and that they just don’t care or thing anyone will notice.

Now, I just gave Bunn a free ride. But, how about them? Why did they fail to impress Cooks Illustrated? Why do high-end roasters who want their customers to own the best brewer often recommend other models, some of the same ones that don’t brew coffee that fall near the SCAA’s box? You might speculate that the other brewer manufacturers don’t care or know how to test, but the high end bean sellers do care and do know how to test. This tells us in a dramatic way that those bean sellers don’t think their customers want coffee that’s “in the box”—the SCAA’s box at any rate.

I’ve tested the Bunn machine. My test results confirm what the SCAA’s box says. The Bunn delivers a nice no-bitterness cup of coffee, one that is very full flavored as far as acidity. My taste observations are that many consumers, including some who buy very expensive beans and grind them carefully before brewing, are now weaned on espresso. The level of bitterness that bothered an honest coffee merchant or taster in 1970 no does not bother this end-user and in fact he desires it. I challenged Cook’s Illustrated on some of their methodology but I spoke extensively with Cook’s Illustrated’s Lisa McManus and they did consult with some honest and notable coffee experts before drawing her conclusions. I think she represents fairly what many consumers would taste. Cook’s Illustrated did not report performing any total dissolved solids tests.

In my opinion, we have here an honest mistake in the making. The sad thing is several industry leaders are trying to do the right thing. Two of the industry’s most noble and honest manufacturers are losing sales because they are adhering to seriously deficient and possibly outdated standards. And, the SCAA is failing to reexamine and update their standards given emerging consumer taste pattern changes.

The risk is what happened to me when I followed the outdated road maps on my GPS this summer. I didn’t reach my goal and someone without guidance did.

by Coffee Kevin | Nov 4, 2011 |

Marcel Duchamp upon viewing an airplane propeller close-up for the first time in 1934. “There is no way painting can compete with this”, was his final proclamation.

While I’m not ready to toss out my favorite objects d’art to collect only assorted industrial designs, I will admit to a certain fascination with inventions of the machine age.

While conventional artworks adorn the walls, or take up space in an otherwiase vacant corner, machines look cool and do thing. Some of the best designed coffee gear is beyond function in its appeal, at least I think so.

Apparently so do others, all gathered together under a canvas tent to outbid each other on some of the treasures sold from the recently closed John Conti Coffee Museum, in Louisville, Kentucky.

So it was, that Patricia Fitzibbon and I flew in for a visit and the possibility of finding some new acquisitions for our growing collection.

Like all great artworks, great industrial designs tell a story, the development and refinement of human invention. For this reason, as much as I detest certain aspects of shopping malls, for example, they are, in effect, modern art museums. Often, their “exhibits” are a better reflection for the life and times of our modern world than the so-called modern art museums, which often appear to me as out of touch embittered mausoleums for the rich, demonstrating only how remote the aristocrat has become from their previous leadership roles. Of course, to deny the rich their role in defining the shopping mall would be in itself a great mistake.

Anyway, back to Louisville, John Conti, Louisville’s premier local roaster, amassed quite a collection over the past 17 years, and had until this year, displayed most of it in a museum open to the public. Although well attended, Conti, probably realizing he had at least one of everything, decided to call it quits, keep a few choice items and allow his booming wholesale coffee business take up the museum space. His museum closed officially in January.

Auctions such as this are as close as most collectors can get to a Las Vegas-style adrenaline rush, and energy to all this that I found quite appealing. I was probably lucky that I forgot my check book, or this issue would be printed on cheaper paper stock. First, the most surprising thing to me is that old coffee tins do very well in commanding respectable or perhaps the word is “outrageous” prices. Save your old Maxwell House cans. Or is it just nostalgia for the time when these brands were still quality names, which means any can after 1075 is likely worthless. For what it’s worth, I saw Saturday morning sales of 1940’s Folgers coffee cans starting at $70. All I know is I was saving my cash for more interesting stuff.

I was glad I did because soon, the bidding moved on to some classic coffee grinders. Those who think latest is always greatest will be surprised when I tell you that coffee grinders were better fifty years ago. Hobart and others built grinders for shops that did a better job on the grinds most customers used then (and still do). The fact that they were so well built is in evidence by the number of them still in existence, and for this reason, they are the bargains of collectors. I was able to pick up a 1920’s Hobart for just $40. As expected, the unit performed perfect grinds, with no adjustment the moment I got it home. I picked up another less-well-known grinder for $12. The ultimate slap in the face of new technology came when the auctioneers raffled off an almost-new Ditting Swiss grinder (current new retail: $1,200) for five dollars. It was a surreal moment, but I have to remember that I was among collectors and, in fairness to the Ditting, it isn’t bad (although it does nothing to unseat the Hobart) it’s just not rare or old.

Many of the action’s participants were members of the Mill Association, a collectors’ group dedicated to old grinders. One of its members told me that he doesn’t even drink coffee, after I asked him which grinder he thought did the most even grind. I still can’t quite understand what possessed him to become obsessed with grinders for a product he doesn’t consume, but, I will say that this group added a strong presence to the ceremonies. There were others who were also coffee connoisseurs and our discussions were lively and fruitful. It was nice to discover that there were others outside the few I know, who realize the value of these products.

This article would be remiss if it did not highlight the presence of Ed Kvetko, former CEO/co-owner of Gloria Jeans Coffees. Kvetko, who long ago told me of his dream of establishing his own coffee museum, was there, along with Gloria Jean herself and his now-endless supply of money, which on at least one occasion, he used to outbid me.

It became first unusual, then irritating, and ultimately humorous to hear the auctioneer’s gavel pound the table, followed by “number five”, Ed’s bid number. After awhile, members of the audience, having no recourse since they were constantly being outbid, behind chanting Ed’s number in unison in sync with the auctioneer. Whereas I and others needed to raise out hands to grab attention of our bids, “number 5”, never out of the interest of the auctioneer, was able to take home all kinds of objects by the slightest raise of his eyebrows to signal interest. Ed’s body language was the only clue one had as to the possibility of outbidding him. At times, when an object would obviously only serve as backup for one already in his possession, Kevtko would sit relaxed in his chair and conveniently stop bidding at just over $20, allowing the middle class participants an opportunity to pick up this or that knick-knack.

Other times, however, Ed would move forward on the edge of his sea, at rapt attention, cigarette dangling from his lip and immediately outbid even the bravest of competitors. Considering that I know Ed has been around the world on similar expeditions, I can’t wait to see his final museum, which he told me he’s locating near his house in Fort Myers, Florida.

After finally outbidding “number five” on a Michael Sivetz-designed (and signed) home roaster, I finally relaxed, only to enter an accidental bidding war with Patricia. Although she was sitting immediately to my right, we became confused during a bid for a 1970’s Kitchen Aid consumer grinder. Knowing how much I wanted it, Patricia entered a bid, which I heard but did not realize she had made. In the tension and confusion, I raise the bid, to the surprise of the auctioneer, who knew we were together, although he realized a good thing when he saw it, and snapped his gavel to close the sale. I glanced over at Kvetko, who smirked.

Now I know why Gloria Jean kept silent the whole time.

by Coffee Kevin | Oct 28, 2011 |

This delightful coffee brewer is commonly called a flip-drip, but actually it is probably mistakenly called a stovetop espresso machine or Moka just as often. It’s a rare animal in American, and, I suspect, most kitchens worldwide.

Which is a shame, because it makes a distinctive cup of brew and, to my sensibilities, suits a number of coffee brewing occasions admirably.

The machine itself has three basic components: half which is filled with water, a second part which features a filter holder for ground coffee and a third part which receives the coffee after it’s dripped through the filter. It is in fact a drip machine in principle.

Disassembled - easy once you do it a couple of times

Fill the part with the tiny hole in it with good water up just short of the hole. Place 27 grams of medium grind coffee in the filter section and screw its cap on tightly. Insert this part into the part containing water. Assemble the other half, the half which will receive the finished brew on top. Place the finished, assembled unit on a stovetop. Turn heat on to low/medium.

As the water heats up it will expand, causing the waterline to rise, just like Al Gore explained in his fine film, An Inconvenient Truth. When the water nears boiling, a small amount will spit out of the hole in the side.

Watch for a bead of water, which means it's ready to flip

Now, shut off the heat and flip the unit over. The hot water will begin to drip through the grounds bed within the second piece. In a few minutes you will have some delicious coffee. Here is how it meets its specs, and why I like it:

Temperature — the temperature is well within accepted limits, although naturally, it varies slightly with just when you turn it over. I found by inserting a narrow thermocouple (tiny wire thermometer) into an operating unit, that it regularly measured 205, at the high end of accepted, but well within limits (195-205 is industry recommendation).

Time — the Neapolitana is grind dependent and can vary slightly depending upon how you “pack” the grounds. I do a little smoothing to make sure they lie evenly, but I do not attempt to tamp it, although I admit it occurred to me as an option. I found the contact time to be around four minutes and could be lengthened by finer grind or tighter packing, but I found no need to do so and I think it would be counterproductive.

Grounds saturation — this unit has a completely inboard filter, which is highly desireable from an engineering perspective. There is no opportunity for grounds to be missed during extraction. They are completely submerged during brewing and even the hot water has no exposure to the external environment before it contacts the grounds and becomes coffee. Its first exposure to the air is once it’s in the lower (post-brewing) half where you will sense the delightful scent from its pouring stem, maybe seeing a little steam as well.

Smooth but don't tamp

The Cup — I tried a number of coffees, but one of my favorites was a (gasp) Starbucks Yemen Sanani, my vote for the best coffee Schultz and Co. has released this year. I happened to wander by a bag of Guatemala from a local roaster, Arbor Vitae, and it delivered pleasing results as well, a lighter roast. The cup from this machine has plenty of body and acidity, although the filter delivers plenty of cup sediment. George Howell is not going to like this machine. I admit I preferred the Bunn NHB for George’s Costa Rica microlot coffee.

On a nice fall day, sitting with your significant other outdoors, this brewer makes a terrific cup and the thick stainless steel keeps the coffee nice and warm, not something I typically include in a review, but it’s a nice extra.

by Coffee Kevin | Oct 24, 2011 |

Back before automatic drip dominated the coffee scene, the most common brewer in kitchens, diners and doughnut wagons was the vacuum percolator. While the vacuum seems like a complicated method, it is actually quite simple, although it’s hard for me to imagine how anyone thought it up.

How does it work? — The vacuum is a bad name, because the vacuum part doesn’t come unit the end. The idea is this: water is boiled in a lower half. As it reaches boiling, a stemmed upper half is inserted. The steam in the lower half expands and pushes the water up through the tube, through a filter and into the upper bowl. This upper bowl contains ground coffee. After a minute of contact where the hot water and ground coffee mix together, the lower half is removed from heat. As the lower bowl cools, this causes a vacuum to form and it drags the upper bowl’s freshly brewed coffee through the filter, down the tube and into the lower bowl. When that’s finished, the upper bowl is removed and you now have a nicely extracted pot of coffee.

Vaculator's propriety clip-in ceramic filter

Stainless steel spring filter

Silex glass rod filter

There are electrified automatic versions, but they work in principal the same way. A second method places the two bowls together from the start, but I prefer putting them together only once the water reaches boiling because I want the water kept away from the grounds until we begin timing the contact time.

Temperature — The vacuum virtually automatically brews at between 195 and 205 Fahrenheit. Even though the water is boiling when you place them together, once the water rises through the tube and begins mixing with the ground coffee, it is usually at 205 or lower. Many people assume its boiling because the water bubbles as it mixes with the ground coffee. This is simply air escaping from the lower bowl, not boiling. Historically, there is evidence that the Coffee Development Group created its standards by observing a vacuum maker, which was very popular at the time.

Time — The time is user controlled, or at least user affected. A certain amount of predictive engineering is expected. You remove the brewer from heat after one minute in hopes the brewed coffee will take three minutes to descend back into the lower bowl, bringing the contact time to a four minute total. This is perfect for a fine grind, and if you use an old supermarket grinder, there will be a setting marked vacuum or “glass” and this is the setting for a four minute extraction.

This is wonderful…when it works. I’ve used vacuum brewers for fifteen years and I can say that 90% of the time, that’s just what happens. But, if there’s any micro gap in the seal between the bowls, if the filter gets clogged with too-fine coffee or for any other atmospheric reason, there is always a possibility of a standstill as the coffee stops descending. Once it’s stuck there are a number of possible fixes. Sometimes I just have to start over. This isn’t very often, but often enough to acknowledge it here.

Extraction — There is no more thorough extraction method known to me than the vacuum. All the grounds are completely submerged in a very short time period and the bubbling water seems to add what is sometimes called turbidity. It’s the idea that fapidly moving water facilitates extraction. Whether this is provable scientifically or not, it sure seems to work, enough so that the vacuum is always my brewer of choice whenever I get a light-tasting coffee. If the vacuum won’t bring out it’s notes, my view is that no method will.

Spent vacuum grounds

Spent grounds show just how effective vacuums are at

extracting every last drop of coffee flavor.

Taste — The vacuum does best with high-acidity coffees. It’s high temperature, that stays high throughout extraction, is just the ticket for light roasted coffees. I found it nigh perfect for Allegro’s Mexican Chiapas and its spicy notes. Armeno Coffee roasters has a number of light roast coffees that performed splendidly with the vacuum, where I was detecting a slight sourness when these same coffees were brewed using a Chemex. The coffee is, if anything, too hot when brewing is completed. If you really like hot coffee, this is your method. I simply use it as a great opportunity to clean the upper bowl while waiting for my cup to come to a reasonable drinking temperature.

Filter notes: No method offers a greater range of filter choices than the vacuum. This particular vacuum, purchased off eBay, features Vaculator’s proprietary ceramic filter held in place by stainless steel clips. The idea, as with glass rods, is to offer a slightly bumpy surface that, when placed in contact with a glass or metal bowl, allows the liquid to pass through, but little or no particulate. You end up with something in between the thick almost-unfiltered French press brew and the cleanness of automatic drip using paper filters. Some would say it’s the perfect compromise. Meanwhile, there are still cloth and paper filtered vacuums as well as a metal spring type that used to be the standard in restaurants. All allow some sediment except for paper.

Cleanup — The vacuum is slightly easier to clean than a French press. While there’s no press to disassemble, there are grounds to either wash down a sink or transfer to waste or, best of all, a compost bin. The worst attribute of the vacuum is the fact that the upper bowl must be removed while it’s still piping hot. If it’s glass, there’s an increased risk that it will break. I’ve broken more than one. Metal ones won’t break, but the hot part is still awkward. There are some ingenious answers to where to put the still-hot, still-grounds-filled upper bowl. A metal one can be laid on its side. The grounds are usually so drained of coffee that they are like a solid mass that will stay put until you clean it.

Conclusion — If you’re looking for the ultimate extraction experience, this brewer may fill the bill. It is not hard to use or clean. The biggest time challenge is waiting for the water to heat up on a stove, or hot plate. Sometimes, I split the water and transfer some to a separate tea kettle to boil, but that’s more trouble than you probably want to go to. If you’re in a hurry, there are other methods that will be more appealing. Even if it happens once, you won’t soon forget a stalled vacuum as described above. Waitresses used to wrap cold towels to attempt to induce the vacuum to cooperate and release the coffee to its lower bowl.

In short, it’s a wonderful method, but I would want another machine as a primary or backup one.

by Coffee Kevin | Oct 21, 2011 |

Blonde Coffee Moment

This was heightened for me reading a sound byte by Robert Passikoff of Brand Keys, a New York City (marketing?) consulting firm. He said, “”It’s just good marketing. If virtually half the people say that the more European, heavier-tasting coffee is not to their liking, why not (do it)?” I could take Mr Passikoff to task for calling it more European – not, the Starbucks roast originated in San Francisco (and Alfred Peet). But, what makes me bristle more is calling it marketing. It might be paying attention to consumer trends but that is not marketing.

Good marketing is leading. Roasters such as George Howell, Oren’s Daily Roast, Counter Culture and Intelligentsia are light roast’s marketing champs. They forged ahead when angel investment groups would have looked cross-eyed that any small-time coffee guys were bucking the Starbucks “secret sauce”, the black roasted product with umami (savoriness). Starbucks marketing was so good so early and it convinced people that overroasted coffee was a virtue, that the only reason it was light roasted was to save weight loss during roasting. Still, sometimes people unchurched in the nomenclature of the coffee industry would simply say Starbucks was too strong, and this was even true among some specialty coffee folks.

Coffee strength alone was never the real problem with Starbucks, although it might seem like it at first glance. Many years ago, after Starbucks first came to rule the Evil Empire of consumer coffee, they attempted briefly to follow the Specialty Coffee Association’s hefty brewing formulas. Consumers collectively gagged and, again in a response to consumers, Starbucks hastily backed off in the brew basket. They made it less strong, but it might be argued that consumers were less in angst about the strength than that they were really tasting the stuff for the first time under the full-strength taste spotlight. The reality and the the real problem was roast. Starbucks came out a while back with a Pikes Roast, which attempted to bring their roast up a few notches lighter. It goes to show just how dark was Starbucks roasting that some, including me, were unable to appreciate Pikes as anything approaching a light roast.

The coffee business likes to pat itself on the back for marketing. It’s as if it doesn’t really believe in its product and are privately saying, “Can you believe people actually like this stuff”? There are two areas where the market (not to say “marketing”) has gone and in both these directions, Starbucks is a follower. So-called slow brew methods, such as Chemex, Hario and other drip techniques have replaced espresso with coffee aficionados. Truthfully, Starbucks never sold espresso anyway but café lattes. Slow brew means filtered coffee, which is really the specialty coffee world’s “special sauce”. Not only is Starbucks burning off the most prized flavors in their roast. They finish it off using an espresso machine. Espresso was invented as a socialist experiment to shorten the Italian coffee break and to bring forth flavors from some of the world’s least costly coffees, not exactly in lock step with the flavor seduction a Chemex can achieve with high-end beans.

Lately, espresso has become the proletariat drink and single-origin slow-brew drip the beverage choice of the literati. Witness Oliver Strand’s precious New York Times columns. Slow brew drip using some single family farm’s beans is cool. This movement was started by high-end consumers, independent farmers who learned to market their coffees using direct trade and, lastly, those high-end coffee guys previously named who stuck it out after Starbucks had attacked them and taken a good portion of their market share. Now consumers flock to them and places like Grumpys, Blue Bottle, Stumptown, all delivering a much lighter roast, and most highlighting the virtues of a small personal pot of coffee brewed per guest or couple.

Meanwhile, Starbucks has done a great job creating community centers. They are modern suburbia’s equivalent of Target, with the same uniformity. They can rightfully claim to have invented or at least won in this competition. The new roast is different. It will allow consumers to have it their way, which is a lighter way. I wish Starbucks well in joining them with the Blonde roast. It might be considered flexible and a smart response. But, it was not a marketing coup.

©2011 Kevin Sinnott All rights reserved.